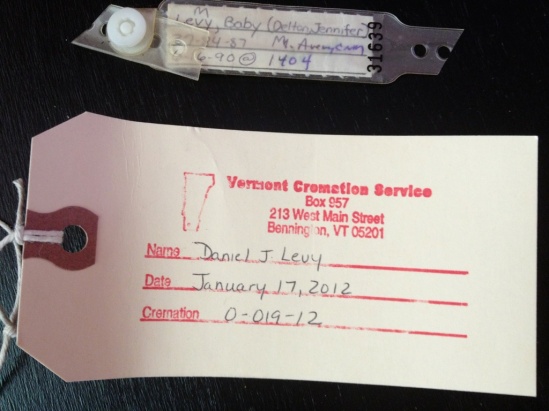

My son committed suicide. He killed himself because he was hopeless. These are words parents never want to say. Two years after the fact, having lived with the brutal reality daily, it still feels surreal. Those two short sentences symbolize a great deal, but they actually explain very little. How do we reduce such a complex explanation to a comprehensible sound bite? We can’t, and yet as humans we crave answers and meaning. I believe the more I try to understand my son’s experience and death from varying angles the more peace I will have.

Mental health experts often talk about survivors moving out of the “Why did they do it?” period to the “How do we survive?” one. I never stick close to scripts, can’t do linear thought and have wandered between these two stages of grief like a sleep- deprived toddler going between parents. I need to understand why Daniel left us. Here’s where I might diverge with typical grief counselors who say, “At a certain point we just need to let go of looking for ‘why’ answers.”

I need to understand as much about Daniel’s suicide as I can. The more I read, the more I realize our understanding of suicide as a society is inadequate and in the process of changing. As with the grief process and my understanding Daniel’s mental illness, I know we can’t bring Daniel back, but my hope is that expanding the conversation about the nature of suicide will help others struggling with these issues, and perhaps help mental health professionals reach more people.

I hold Daniel’s mental illness responsible for the “hijacking” of his brain. Discussing his exit, his leaving us, his murder of his own body and his ending of his life experience merely as a “choice” and moral issue, both trivializes his action and reduces it to the realm of a simple, willful act.

My position on my son’s mental illness is not a controversial one. He likely suffered from bi-polar disorder with schizophrenic features. Doctors were a little less willing to see the dissociative, psychotic episodes as schizoid, but no one I talk to about the profundity of his suffering, it’s duration and it’s depth, believe it could easily have been healed, erased or managed. The feedback I have received socially is concordant with my experience in dealing with the realities of my son’s plight. This openness in discussing mental illness (a big shift from 20 or so years ago) has helped me and my family process the grief related to Daniel’s death.

But the subject of suicide is much more understandably contested—and a feature of Daniel’s struggle that is the most tragic and troubling.

Very few people I know said or intimated that his mother Jennifer and I could have done more than we did to prevent his suicide. Fewer still suggested it was a “cowardly act” — the socially accepted/morally-mandated response and belief in our society for years that may have prevented/ shamed some people from killing themselves for fear of looking weak and selfish. By-and-large people have understood that Daniel’s death was a tragic perfect storm of a tenacious, cruel disorder, the fragility of a developing adult mind in wrestling with the onset of the beastly illness and inadequate systemic and knowledge features of our health system. No one says he made the “right decision.” Suicide prevention groups believe we should try to save everyone, and hope that though some will slip through the safety nets, if we continue talking about suicide, giving people access to mental health resources, we will reduce the numbers of suicides. I support their work wholeheartedly.

But I think society as a whole is in the throes of large-scale reframing of our understanding of suicide.

Jennifer Michael Hecht is leading the charge in a position calling for a greater sense of personal responsibility in our duty to the social contract to reject suicide. In her recent book Stay, she argues that Christianity in Western Civilization, while authoritarian and frequently xenophobic and violently hateful, created a bulwark of interdependence and taboo that made suicide a more difficult option. The Enlightenment with its celebration and institutionalization of individual freedom and questioning of religious authority gradually contributed toward a crisis of community, spirituality and a weakening of taboos about suicide. Her argument is historical, somewhat statistical and focuses on a number of artist suicides.

“As I examine the history of how, in the West, we have understood self-killing, I also will put forward what might seem to be a contrarian position, a nonreligious argument against suicide. It is a philosophical argument but parts of it can or even must be told in terms of history, and parts must be demonstrated through modern statistics. One of the arguments I hope to bring to light is that suicidal influence is strong enough that a suicide might also be considered a homicide. Whether you call it contagion, suicidal clusters, or sociocultural modeling, our social sciences demonstrate that suicide causes more suicide, both among those who knew the person and among the strangers who somehow identified with the victim. If suicide has a pernicious influence on others, then staying alive has the opposite influence: it helps keep people alive. By staying alive, we are contributing something precious to the world.”

Noble. Hopeful. But she doesn’t really attempt to explain the nature of mental illness as it relates to suicide. She doesn’t blame but she reduces suicide to a sort cost/benefit utilitarian rationalism.

In trying to understand Daniel’s suicide, the notion of “choice” is hard to escape. How could a young man surrounded by loving friends and family do this? How could a person so hyper-sensitive to other people’s and non-human animal feelings choose to end his life, negatively emotionally impacting so many and rupturing the social fabric so severely? He knew his sisters, whom he loved dearly, would be impacted for life by his “choice,” didn’t he?

I went through his computer after his death and saw in browsing history and tabs on his computer he had been visiting numerous suicide prevention sites…but he was also conferring with end-of-life mercy killing folks and websites and watching documentaries on suicide. He was weighing his decision, vacillating back and forth, wasn’t he? According to Hecht, Daniel chose to leave because staying was too hard. He lacked the will to tough it out, so to speak.

I find this framework inadequate for understanding Daniel’s death and for looking at suicide as a phenomenon.

Psychologist Thomas Joiner poses a new framework that argues that suicide is not simply an act, but rather it is a process. His research has focused on the brains of suicidal people. The capability of suicide requires fearlessness. Joiner sees a connection between the self-damaging behavior of anorexia and suicide. Individuals suffering from anorexia are essentially overcoming the fear of starvation and bodily harm, and their self-destructive behavior often has lethal results.

For Joiner the fear regulator in the brain, the amygdala, is the key to understanding the leap from thoughts of perceived burdensomeness by suicide decedents to the actual killing. Far from being an impulsive act, as suicide is often misunderstood to be, there is essentially a training of the brain’s amygdala to be unafraid of self-harm.

So here are the features (in no particular order) of Daniel’s state-of-mind, I believe that may have factored into his suicide:

- A possible shift/alteration in his lymbic system, the amygdala fear regulator in particular, that allowed Daniel to lack the fear of death and self-harm.

- A perceived sense of burdensomeness –Daniel believed he was doing the world, his parents in particular, a favor by leaving.

- A perception that the only way to silence the evil voices in his mind was to kill himself.

- An absolute absence of hope. I see this as a real existential factor. There was no cosmological explanations or religious/moral-ethical/spiritual tenets and frameworks that could help Daniel find hope. He read a huge amount in his last year about world religion and brain science. None of the historical wisdom resonated enough to keep him hanging on.

- His mind had essentially been hi-jacked by progressive mental illness. Was it bi-polar disorder? Maybe early onset schizophrenic features? We may never know the exact nature of the mental illness issues Daniel was struggling with—health care professionals were very cautious in terms of diagnoses.

- One other possibility was the medications he was on. I don’t really want to go down the rabbit hole of whether specific meds he used or refused to take had some kind of impact on his state of mind, but I think his refusal to take meds especially in the last year, or at least his spotty use of them, probably impacted the big picture. He tried a number of pharmacological options to deal with mood and behavior and found them all distasteful and unpleasant in terms of side effects.

These 6 factors help me to start to make sense of the complex mixture of environmental, potentially genetic/bio-chemical changes, internal psychological, and clinical/diagnostic issues around Daniel’s suicide. I think they also reveal the notion of patterns of cause rather than definitive easy answers.

All of the individual pieces are complicated—but in some ways the issue of hopelessness in the equation provides the most painful and vexing component of the big picture. Hope is the only thing that really stands between our lives and The Void.

Perhaps I will start to talk about this behemoth in the next installment.

Thanks for reading these dispatches as I process my grief and understanding.

Sincerely,

Adam